Sunbaked

“Dave Elba.”

My hair stood on end, a shiver raced down my spine and a lump came to my throat. What could be happening right now? What would the outcome be? What would happen? What could be written on that paper?

As I looked at him holding what would determine my fate for a few years to come, I felt a sudden irritation. He was holding it so flimsily and carelessly like he could care less that the next words that would come out of his mouth would either make or mar my life.

“Yes?”

He looked up at me and looked back down at the paper, disappointed. “You’re Dave Elba?”

What was that hint of disbelief I could see on his face? At that point, all I wanted to do was launch an attack on him and seize the paper from under his judgmental eyes.

“39%. That’s a fail.”

The air suddenly became so thick and it was suddenly difficult to speak. Or even breathe. “Sir? What did you say?”

“39% Dave Elba.” He said in such an offhand manner that refused to acknowledge the weight of the words he had just spoken.

“Samuel Ad…” And he moved on to the next person like he had not just ruined my life. I couldn’t hear anything anymore but just before I moved out of the hall in a haze, I heard shouts of jubilation. Someone had passed the entrance exam. That person was not me.

***

“What do you mean by you failed the test?” My father bellowed.

“That’s what they said.”

“But you have never failed a test in your life. Why this one?” My mother whispered quietly, still struggling to come to terms with the reality of my news.

“I’m talking to you, young man! What do you mean by you failed the test?”

“I went to the office for the second screening. They only allowed people that had passed the first test. The person in charge looked at my name and told me I didn’t pass. He said I had 39% and the Pass Score is 50%.” I explained as plainly as I could, even though I knew that the last thing my father wanted was an explanation. He was more vocal of his frustrations and disappointments than my mother was, so he was repeating several times hoping the repetition would make it make sense.

My mother just sat with a sad look plastered on her face, like we had just lost someone. Although she didn’t understand the full implications of what was happening, she knew how important it was to me. We had made all the plans already. Since the company was far from my parents’ house, my parents had suggested I moved into a studio apartment near the office.

My father had already been making calls to some of his friends with properties around the area. He even promised to get me a new laptop to make my job easier. It had lifted up the mood of the house, and everyone was expectant, happy. Now, this.

After my father’s shouting parade, the house became awkwardly quiet. Whenever he didn’t have someone to join him in a shouting match, he usually went sober and quiet. My mother knew this, and I had come to understand it growing up.

So, I kept quiet while he blamed me for failing even when I had never failed a test in my life. Not to talk of one as life-defining as this. I kept quiet and watched him, while I cried painfully inside. When we had all been quiet for about five minutes, I mustered the courage to ask,

“Can I go inside now?”

When I didn’t receive a response, I shoved my hands in the pockets of my hoodie, and walked to my room, damning the consequences.

***

The next week went by in a haze. The house remained awkwardly quiet and all our conversations in the house were kept to the necessities.

One night, my mother came into my room, clad in her nightwear, with a small scarf holding tightly to her loose braids. She looked at me and looked at my room. I had not cleaned the room in a few days and the air smelled of dirty underwear and stale food. I also had my dirty laundry strewn across the carpet and I was still wondering why my mother had not said anything about it.

“Have you eaten?”

“I’m not hungry.”

“I kept rice for you last night and I still found it in the kitchen today.”

“Yeah. I was not hungry.”

She sighed. I saw her struggling between her African mother instinct to toughen up and force me to do what I’m supposed to do and her need to comfort her son who just suffered a heartbreak. She stayed quiet while I stared at my laptop’s home page. There was nothing to do at that point except stare at the crisscross metallic design I used as my screensaver.

“Are you still feeling bad about the test?” My mother finally broke the silence.

“Somehow.” She didn’t say anything. “I just feel dumb.”

She gave me a small smile. “You’re my smart boy. Don’t let one test define you or make you feel less of yourself.”

I was expecting her to say that, and so, I just sighed. “It’s easier said than done.”

“See, let me tell you. You are intelligent. You never brought me shame when you were in school. I would always go to your end of the year parties with a big polythene bag so I would have enough space to pack all your prizes. I never went home without a full polythene bag. You never brought me shame, and I stand by that.”

I looked up at her. “And now?”

“What is yours will come. You hear?“

“Yes, mummy.”

“Don’t mind your father. He was really looking forward to it, but he will get over it. When he comes today, we’ll go together to talk to him. You hear?”

“Yes, ma.”

Saying ‘I love you’ to your child in an African household is as hard and impossible as a three-month-old baby cracking a palm kernel nut. If it had been easy for her to say, I assumed that would have been the perfect moment for my mother to tell me how much she loved me. But the beauty of the love of an African parent is that it is expressed in actions that would forever mean more than their words could ever convey. She put her hand on my head and used her index finger to scratch my ruffled hair that was overdue for a haircut.

“Thank you, Mama.”

I only called her Mama when I felt so overwhelmed with emotions that I wanted to cry.

“Oya, come and eat. I cooked yam and egg. I even put fish and carrots, like the one we saw on TV that day that you liked.”

That was the surest and sweetest ‘I love you’ my mother could give me and I couldn’t ask for more. I didn’t need it.

***

Two weeks later, I was in my room staring at my laptop and thinking of the next step to take. I had been so sure of getting into Sunbay Technologies that I had not made any plans in case it didn’t fall through. When I felt my head begin to hurt, I turned on the laptop and opened up my Scrabble app. Playing it always helped me relax. Just then, I heard my phone ring.

“Hello? Hello?”

“Hello? Who’s this?”

The voice on the other end sighed in relief. “Thank God. I’ve been trying to reach you for a few days now.”

“Sorry. I was a bit occupied.”

“Okay, Okay. This is Adebowale from Sunbay Technologies. I’m the Human Resources Director.”

Sunbay Technologies? What bad news do they have for me this time?

“I’m listening.” At this point, nothing could hurt me anymore. I was so uninterested in whatever he had to say that I put the phone on speaker and dropped it on my work table while I got back to playing Scrabble on my laptop.

“It’s about your test results.” I paused for a minute.

“I’m listening, Mr. Adebowale.”

“Okay. I’m calling on behalf of the company to apologize. On the day of the screening, you were given a wrong test score by one of our interns. We deeply apologize for the error.”

I couldn’t speak. “Mr. Dave?”

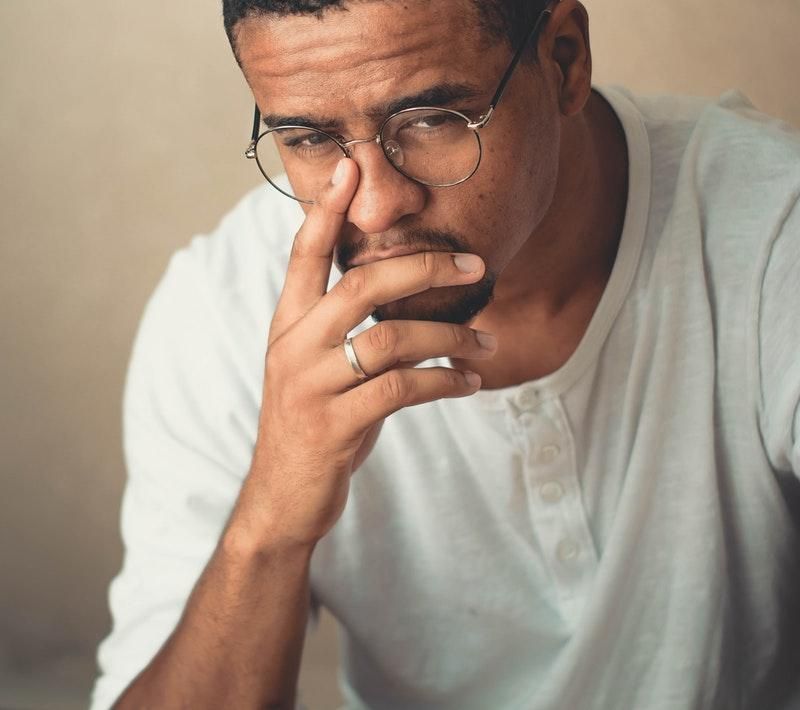

“I’m here.” My palms had become pools of salty water at this point, and I started feeling a crazy itch inside my eyeballs. I took off my glasses, but still, I was almost afraid to ask. “Did I pass?”

“A whopping 93% sir. The highest score yet. It’s why we noticed your absence during the next level of the screening exercise. We deeply apologize sir and we were hoping you could still come in to complete the screening.”

93%? Me?

“Mr. Elba?”

“Hmmm?” I couldn’t speak, for fear that I would scream my lungs out and probably give my mother a heart attack.

“Can you still come in, sir? We hope this doesn’t mess up any of your plans.”

“Yes. Yes. I will come.”

Sunbay Technologies, here I come! Silicon Valley, here I come! Google, here I come!!

All pictures are from Pexels and no attribution is required.

She's an African, Afro-American breed. She's way too radical in her writing style. She adds in a little childish nature to the mix, representing all you want to be but can't.